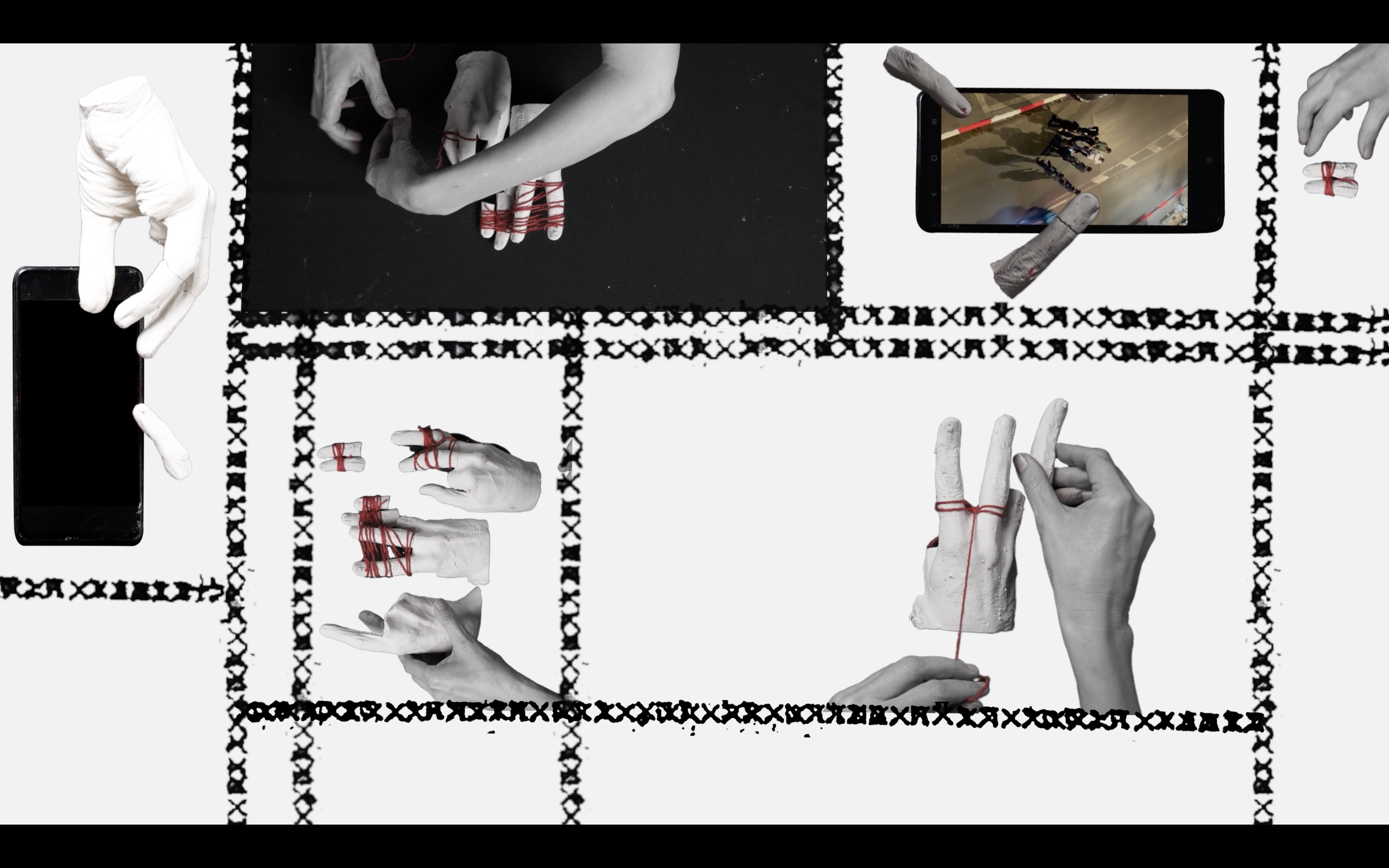

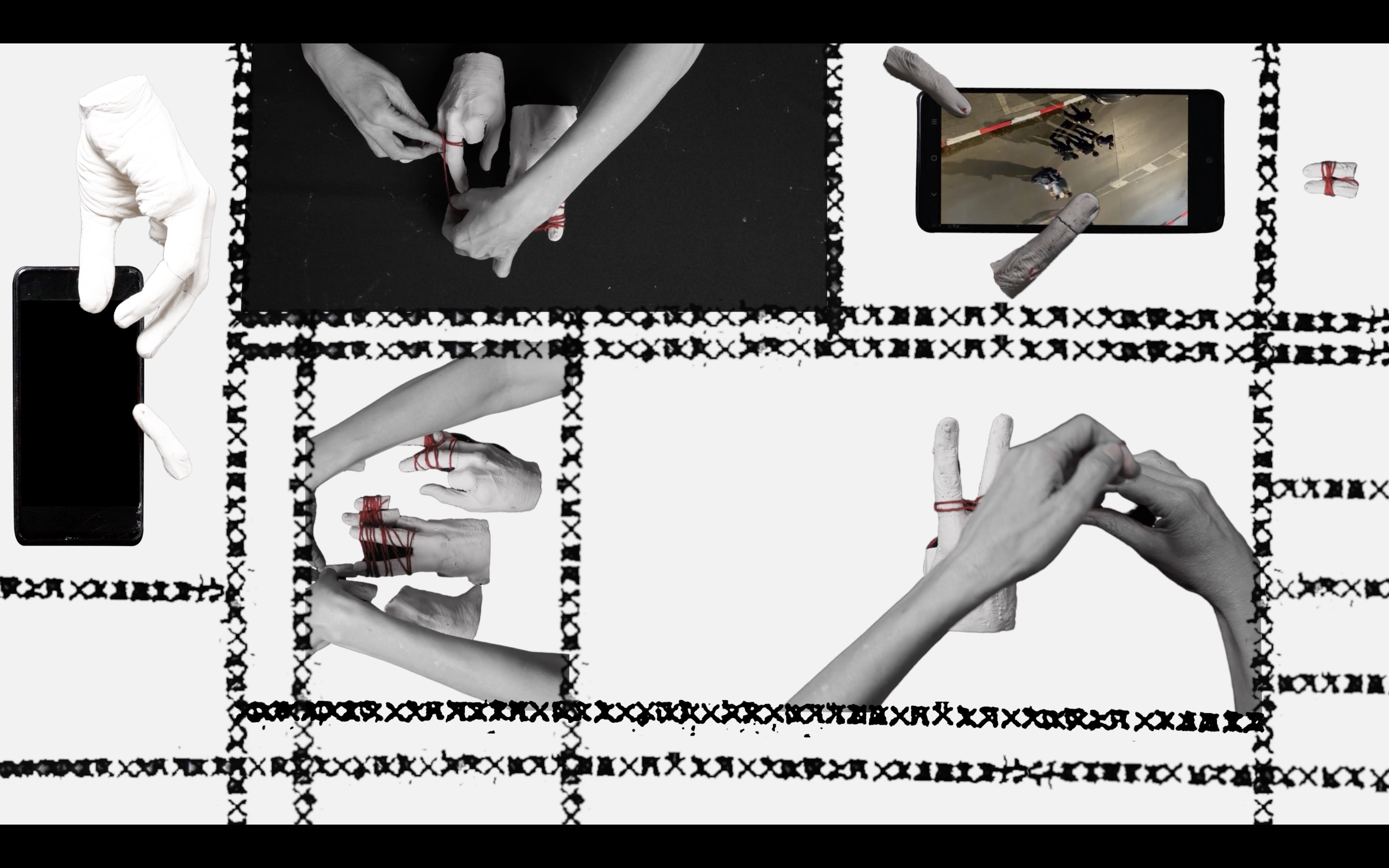

Minor Inscriptions , 2025, 15 min 16 sec

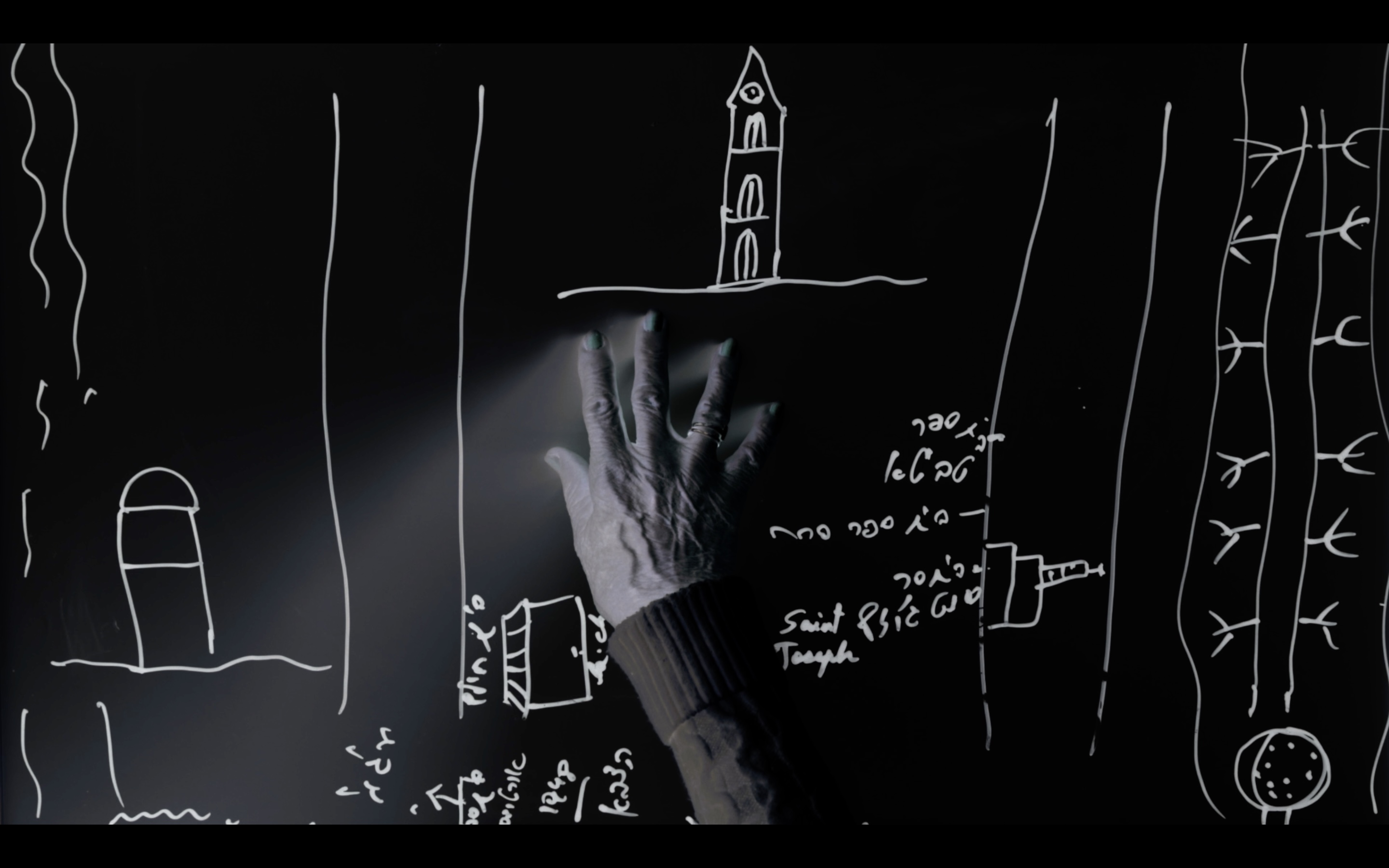

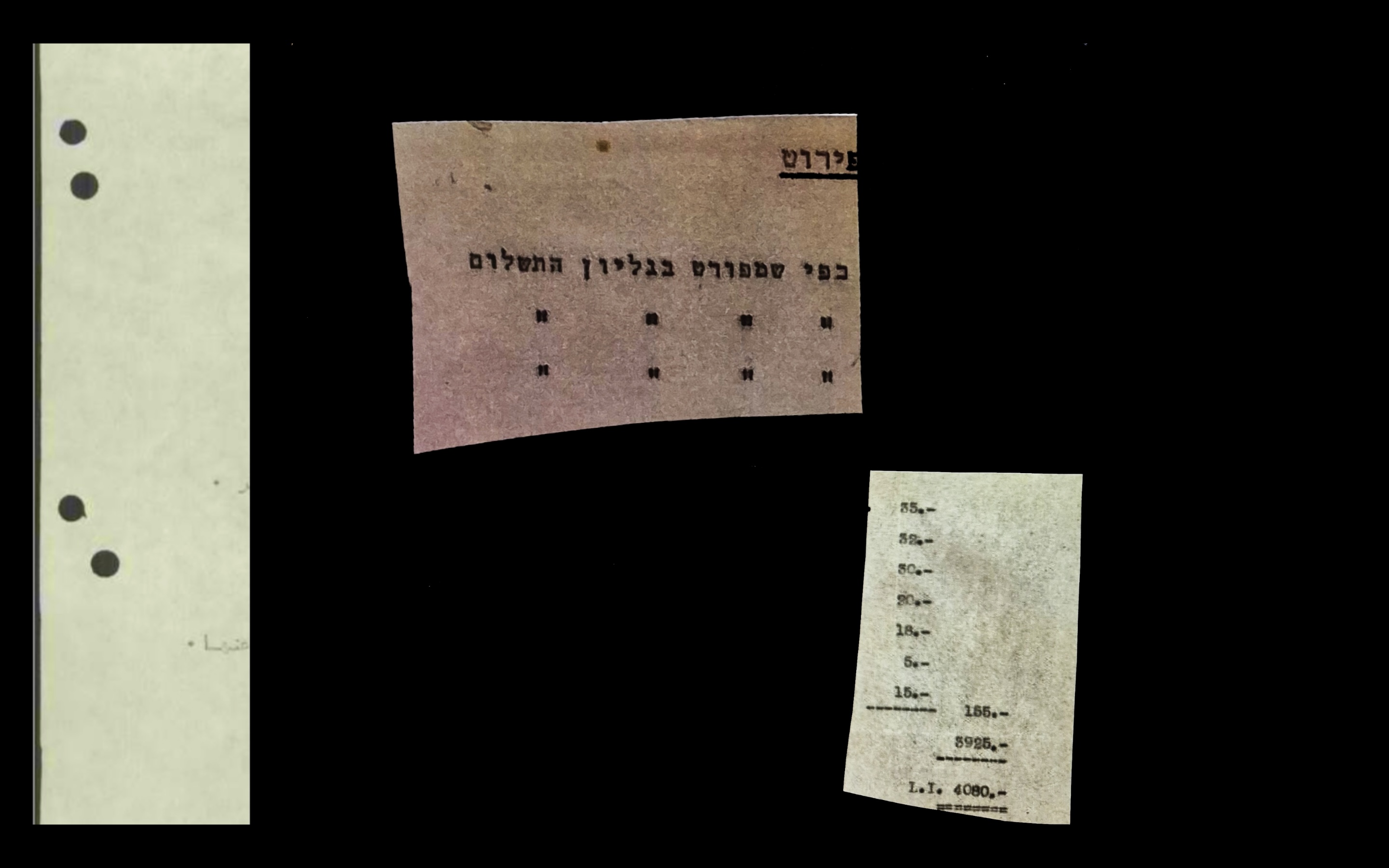

Minor Inscriptions investigates the invisible borders imposed by martial law in Jaffa between 1948 and 1950. Using archival documents, maps, testimonies, and video fragments, the work traces boundaries that have vanished physically yet remain embedded in current spatial, technological, and political infrastructures, actively shaping the present.

The work focuses on “bureaucratic violence”: a system of control based on the administrative regulation of movement and access, where every passage through the city requires permits. How can violence operate through administrative practices like numbered lists and statistical databases?

The work takes place on a desk and filmed from above – the overhead view often associated with a position of authority. Documents, maps, physical objects and mobile screens are arranged across the desk. A multilayered editing of photos, videos, and images creates a dynamic and timeless map of Jaffa/Yafa, where freedom of movement is managed capriciously and the physical and symbolical borders remain palpable, even if they are invisible. The permits, checkpoints, and detainments did not go anywhere, they only took on a different shape.

Although martial law officially ended, its logic persists, continuing to structure contemporary urban life.

Hand to Mouth, a photo series, 2025 and Surviving Images, a video based on recorded lecture-perfromance, 2025

As part of Unfolding Desire at Trieste Contemporanea

A project by AiR Trieste in partnership with La Collina Social Cooperative,

Trieste Contemporanea, and Griffin Art Projects

Curators: Francesca Lazzarini and Elham Puriya Mehr

Artists: Ofri Cnaani and Evann Siebens

In collaboration with: Escuchame and Collettivo Marte

Unfolding Desire is a research project that stems from the encounter between artistic practices, archive theory, memory, and shared experiences to imagine possible futures in a time marked by the re-emergence of authoritarian impulses and normalising logics.

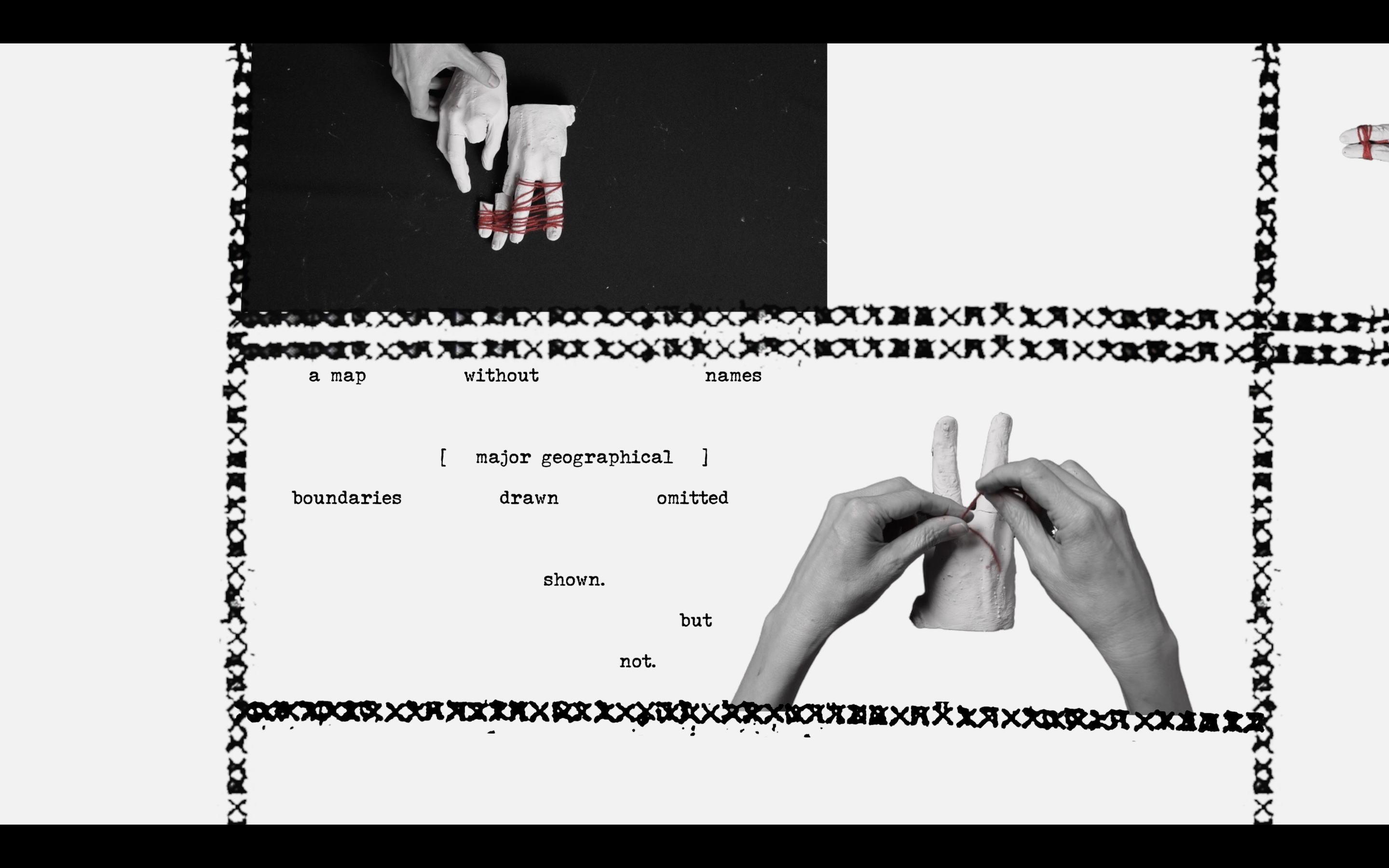

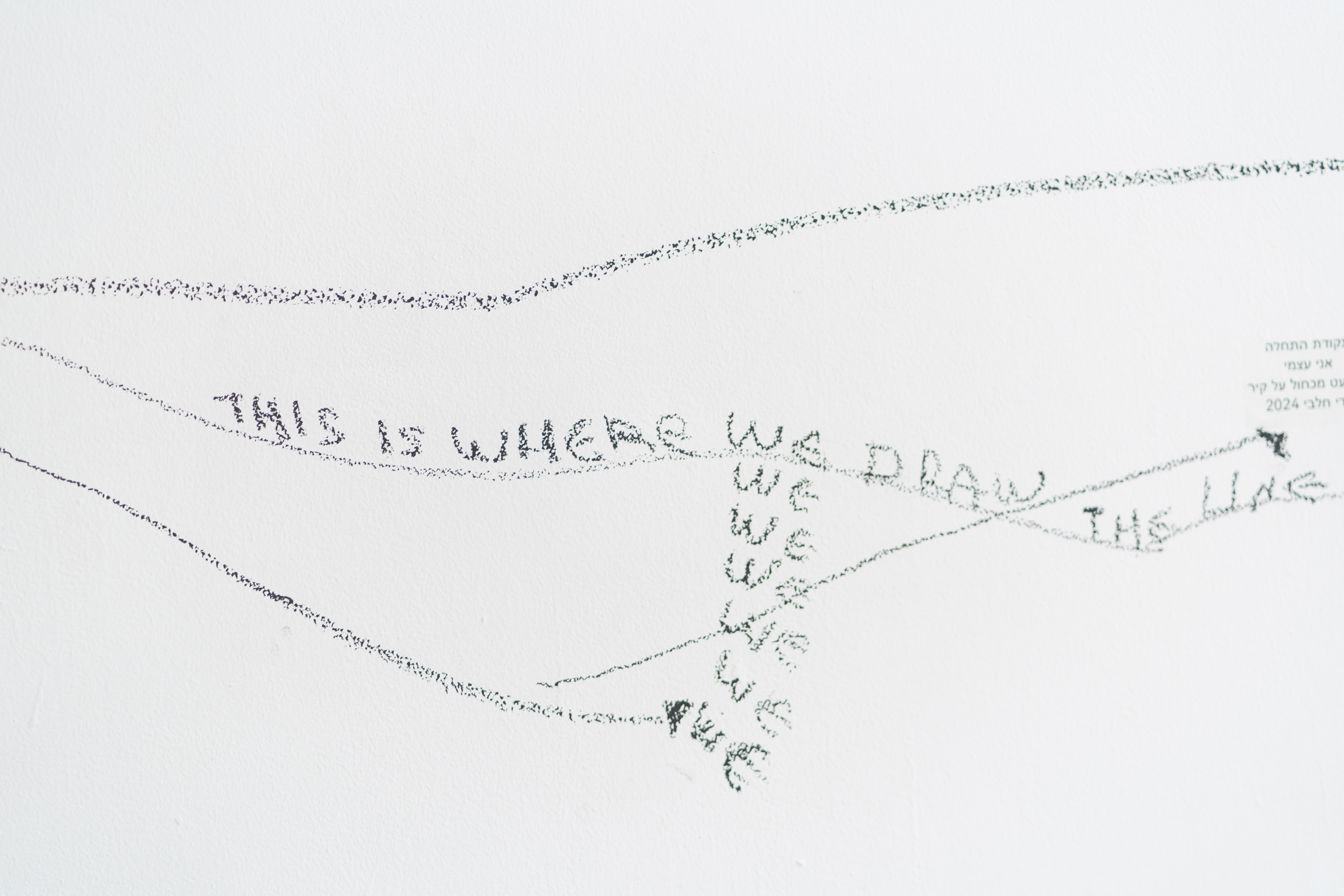

Ofri Cnaani’s work engages with the lived residues of deinstitutionalization to rethink archival, classificatory, and digitization practices. Informed by San Giovanni’s relational model of care, where healing arises through proximity rather than confinement, her project approaches the CDD as a living, affective field rather than a static collection of materials. Through the involvement of Escuchame and Marte collective participants in a workshop held by the artist, documents and images become tools to think with, hold with, and act with. While the CDD has always been subject to the instability of political and economic agendas, the partial digitization envisioned by Cnaani resists stabilizing an institutional past. Instead, it proposes a method grounded in adjacency, memory, collaboration and embodied presence. Rejecting generic metadata systems that flatten context, the workshop and the resulting artworks treat digitization not as neutral transfer but as a socially embedded act: shaped by decisions about what is preserved, by whom, and for whom. Inspired by Aby Warburg’s “law of the good neighbour,” which arranged books by proximity of thought, not taxonomy, Cnaani extends this principle to images, placing them in relation, where meaning emerges in between and in with-ness. She does this in the photographic series Hand to Mouth (2025), where her hands engage both with those of the workshop participants at San Giovanni and with the gestures from Bruno Munari’s book Speak Italian!, highlighting the affectiveness of hapticality as an alternative form of engagement. She continues this approach in the video Surviving Images, where materials selected by participants are mobilised to construct a new narrative. Through collectively being and engaging with images, her work resists extractive, colonial logics of classification, now echoed in AI systems, and instead frames digitization as a performative, situated act of care, shaped by collective negotiation and grounded in micro-struggles for access and specificity.

A segemnt from Surviving Images video that is based on a lecture-perfromance:

We met again on May 14th, 3PM. I was still on the screen. Guillermo, Marina, Diego, Renato, Pavel, Mad Max, Cecilia, Samuel, Emidio, Roberto, Eduardo, Diana and Lydia. Also, Francesca, Michaela , Elham, and Evann. Nothing ever prepared us to speak about proximity from far away, but we were making proximity from far away.

We spoke about how images speak to one another, how do they answer back? And about Aby Warburg’s intervals, the spaces between images that have, he proposed, their own Iconology. They are units of meaning, not a gap or a void, but a pause. A much-needed pause that makes room for a conversation. I asked you to choose images from last time, place them and connect them. Making the intervals work, making them speak with their hands, singing the song of the ones who are supposed to be silent. And you were making the intervals work. You did, and I learned that from you.

That art is spreading everywhere

That art will save us

That the question is the answer. And the answer is in the question

That no one wants a professional treatment, but equal rights.

That your body belongs to you

That freedom heals

That the body heals in its freedom

That colours and crayons are acts of resistance

That Art is an act of residence and an opportunity for communication

That Art will save us

And that is spreading everywhere

That Marina is a work of art herself

That today you feel like the main character of your life

That, unless a cure is without money, you are not free

That horses have eyes on their side (but I knew this one already)

That we should always pay attention to the predators.

That Insanity is a paradox

That the centre of documentation is an actual resistance

That the institutions would like them to be erased

That you brought freedom to the inmates in Leros, only speaking with your hands

That 100 patients in Leros had fled beyond the walls. That intervals of freedom are in the invention of escape

Thats hands is the language when no language is found

That love is the message.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Unfolding Desire Read full curatorial text by Francesca Lazzarini and Elham Puriya Mehr

In an era marked by the troubling resurgence of populist and authoritarian tendencies worldwide, Unfolding Desire brings together artists, curators and practitioners from different experiences and conditions to delve into the affective and sensorial territories of the archive where new forms of resistance can be imagined and set in motion. Mobilizing the concept of desire for the future, the project – organized by Air Trieste in partnership with Trieste Contemporanea, the social cooperative La Collina, and Griffin Art Projects – unfolds through collaborations with the Documentation Center (CDD) Oltre il Giardino of San Giovanni ex-psychiatric hospital, the Marte collective, and the programme Escuchame by Radio Fragola, engaging with the radical notion of lunatic desire as a portal for envisioning alternative futures. It asks: What creative methods can we develop to explore, practice, and sustain 'desire' and transfer its potentialities to the future? Through a constellation of workshops, residencies, video projects, events, and an exhibition, Unfolding Desire aims to develop new critical and somatic tools for imagining and practicing care, cultivating new terrains for collective futures through research into the materials of the CDD.

Addressing the global resurgence of fascism, Brazilian psychoanalyst and scholar Suely Rolnik identifies desire as the central site of struggle within the neoliberal and financialized phase of capitalism. In this context, Rolnik describes the "coup," the seizure of power by neoliberal and neoconservative alliances, as a mechanism that captures and immobilizes desire, preventing it from sustaining its insurgent, world-making force. Rather than fueling creative transformation, under this regime, desire is trapped, neutralized, and instrumentalized to reinforce domination and capitalist accumulation. Resisting this capture requires activating the unconscious through the action of micropolitics, to make it a space of potentiality, where lunatic or unruly desires can imagine and enact new futures. It is in this terrain that collective practices of care, resistance, and invention must take root.

This aim has encouraged us to initiate our collective resistance by delving into the material collected by Oltre il Giardino about the experience and history of the ex-psychiatric hospital of San Giovanni Park, which offers a unique vantage point for examining the radical transformation of psychiatric care in the 1970s. Under the leadership of Franco Basaglia, this revolution dismantled the oppressive structures of institutionalization, proposing instead that care must be woven into the very fabric of society. For Basaglia, healing was inseparable from emancipation: transforming practices of care meant transforming society itself. His work culminated in the abolition of coercive treatments such as shock therapy and physical restraints, leading to Italy’s landmark Law 180 in 1978. It was later carried forward by figures such as Franco Rotelli, turning Trieste into an example of a collective mental health system grounded in ethical responsibility and inclusivity, what Pantxo Ramas refers to as an ecology of care. In this ecology, art has always played a relevant role, meeting with the struggles for rights to overcome stigmas and prejudices and to open new cultural, educational, and productive horizons. This setup allowed patients and workers to re-imagine and express their dreams for a new future through artistic means. It encouraged experimentation, invention and imagination and enabled social change, transformation, and becoming: in a word, unfolding.

In The Fold, Laura U. Marks writes, “as Gilles Deleuze, often with Félix Guattari, emphasized again and again…the relevant category is not Being—what exists—but Becoming—what changes.” In resonance with this view, we understand unfolding as a dynamic process that draws the perception of our senses towards the seemingly nonexistent as it rolls into being. In the project, it is through unfolding that artistic practices bridge archival images, their anecdotes, and latent stories with the body, generating profound affective responses, shock, joy, sorrow, or subtle resonances that function as embodied forms of knowledge. As Marks notes: “You can reach into the most compressed thing – a rock, an emoji, a preserved lock of hair, a frame of film, a name on a black Zoom screen – to unfold its story. From world to medium to us, unfolding expands and contracts the connective tissue like an accordion”, enabling a dance with ghostly traces and the invisible to take form.

For Unfolding Desire, the archive is not merely a structure of memory but a site of unfolding; it is a projection of desire, not only for the past but for a future anchored in what can be remembered, recovered, and reactivated. This is an attempt to script the future, to extend life into what is yet to come. Still, desire remains incomplete, marked by loss, distortion, and omission. The unfolding desire of the archive insists that the most radical futures are those that resist full capture, that remain elusive and emergent. We whisper of another kind of future, not yet legible, but already present in bodies, atmospheres, and affects, a horizon vibrating with the possibilities of what might still come.

Through diverse practices, visual, performative, sonic, and relational, the artists involved in the project trace how desire can be wrested from capture, re-attuned to the forces of life rather than domination. They invite us into spaces where new subjectivities may emerge, where the unconscious is not merely a terrain of regulation, but of emancipation. In doing so, they insist that the struggle for a livable future must begin here, in the micropolitical folds where desire is still unfolding.

Ofri Cnaani’s work engages with the lived residues of deinstitutionalization to rethink archival, classificatory, and digitization practices. Informed by San Giovanni’s relational model of care, where healing arises through proximity rather than confinement, her project approaches the CDD as a living, affective field rather than a static collection of materials. Through the involvement of Escuchame and Marte collective participants in a workshop held by the artist, documents and images become tools to think with, hold with, and act with. While the CDD has always been subject to the instability of political and economic agendas, the partial digitization envisioned by Cnaani resists stabilizing an institutional past. Instead, it proposes a method grounded in adjacency, memory, collaboration and embodied presence. Rejecting generic metadata systems that flatten context, the workshop and the resulting artworks treat digitization not as neutral transfer but as a socially embedded act: shaped by decisions about what is preserved, by whom, and for whom. Inspired by Aby Warburg’s “law of the good neighbour,” which arranged books by proximity of thought, not taxonomy, Cnaani extends this principle to images, placing them in relation, where meaning emerges in between and in with-ness. She does this in the photographic series Hand to Mouth (2025), where her hands engage both with those of the workshop participants at San Giovanni and with the gestures from Bruno Munari’s book Speak Italian!, highlighting the affectiveness of hapticality as an alternative form of engagement. She continues this approach in the video Surviving Images, where materials selected by participants are mobilised to construct a new narrative. Through collectively being and engaging with images, her work resists extractive, colonial logics of classification, now echoed in AI systems, and instead frames digitization as a performative, situated act of care, shaped by collective negotiation and grounded in micro-struggles for access and specificity. These new works dialogue with a previous series by the artist, Statistical Bodies (2020-2023), that explores questions of organic-electronic care, body datafication, and the incomputable. By paying attention to the impulse of capital as it intimately circulates the body, the works identify moments that hold new nexus of data, extraction and the corporeal, but also carry the potential of friction, or rupture of the seamless flow of those transactions.

Like Cnaani’s, Evann Siebens’ works emerge from a close engagement with the images of Oltre il Giardino and the people who animate San Giovanni Park on a daily basis. The artist’s body plays a central role; it is through an embodiment of the CDD materials that she creates a suspended space of encounter, where knowledge, desire and new possibilities can emerge. The series Embodying the Unarchivable (2025) resonates with the idea of that which reveals: embodiments of fears, fantasies, and not yet formulated aspirations—always excessive and irreducible. The result of this process is a series of layered images incorporating performative gestures and hybrid figures that compress multiple temporalities into singular frames—bodies in flux, saturated with movement and transformation—to expose the materials to deeper emotional and affective engagement. Siebens’ research mobilizes the notion of the uncanny, read as a battleground of ghostly forces constantly made and unmade. Through her works, the artist evokes it, transforming its monstrous connotations from a site of stigma into a liminal presence that disrupts order and reawakens forbidden desires.

Even in the creative process of Performing the Unpredictable (2025), the artist's body offers itself as a convergence for multiple forces. The work includes a live performance—realized in collaboration with sound artist Samuel Codarin and actor Pavel Berdon—and a video piece. Recorded at San Giovanni Park during the residency in Trieste, the video features Berdon, Codarin, Diego and Renzo Porporati, Maximillian Rosani, Guillermo Giampietro, and many other participants from Escuchame. It reflects Sieben’s conception of the camera as an extension of her own limbs. The sense of interaction, complicity, and relationality that emerges within and thanks to the moving images is further intensified in the live performance, where the video is projected onto the artist and Berdon’s bodies, becoming a conduit, just as the live sound performed by Codarin acts as a connective tissue. The improvisational interplay between bodies, images, voices, and sound conjures a charged moment of anticipation, presaging the repressed to resurface and the unexpected to come.

With its complex structure, composed of different events and fleeting moments of collective exchange, Unfolding Desire maps its processual and affective terrain. More than a project, it becomes a living practice that reclaims the imaginative force of desire through shared gestures, resonant bodies, and relational encounters. At its core lies a commitment to collective recognition and transformative care, where madness is embraced not as a deficit but as a generative force. By centring embodied participation and affective attunement, Unfolding Desire opens a space for imagining otherwise—a space where alternative futures can be felt before they are fully formed, and where new forms of life may quietly take root in the folds of togetherness.

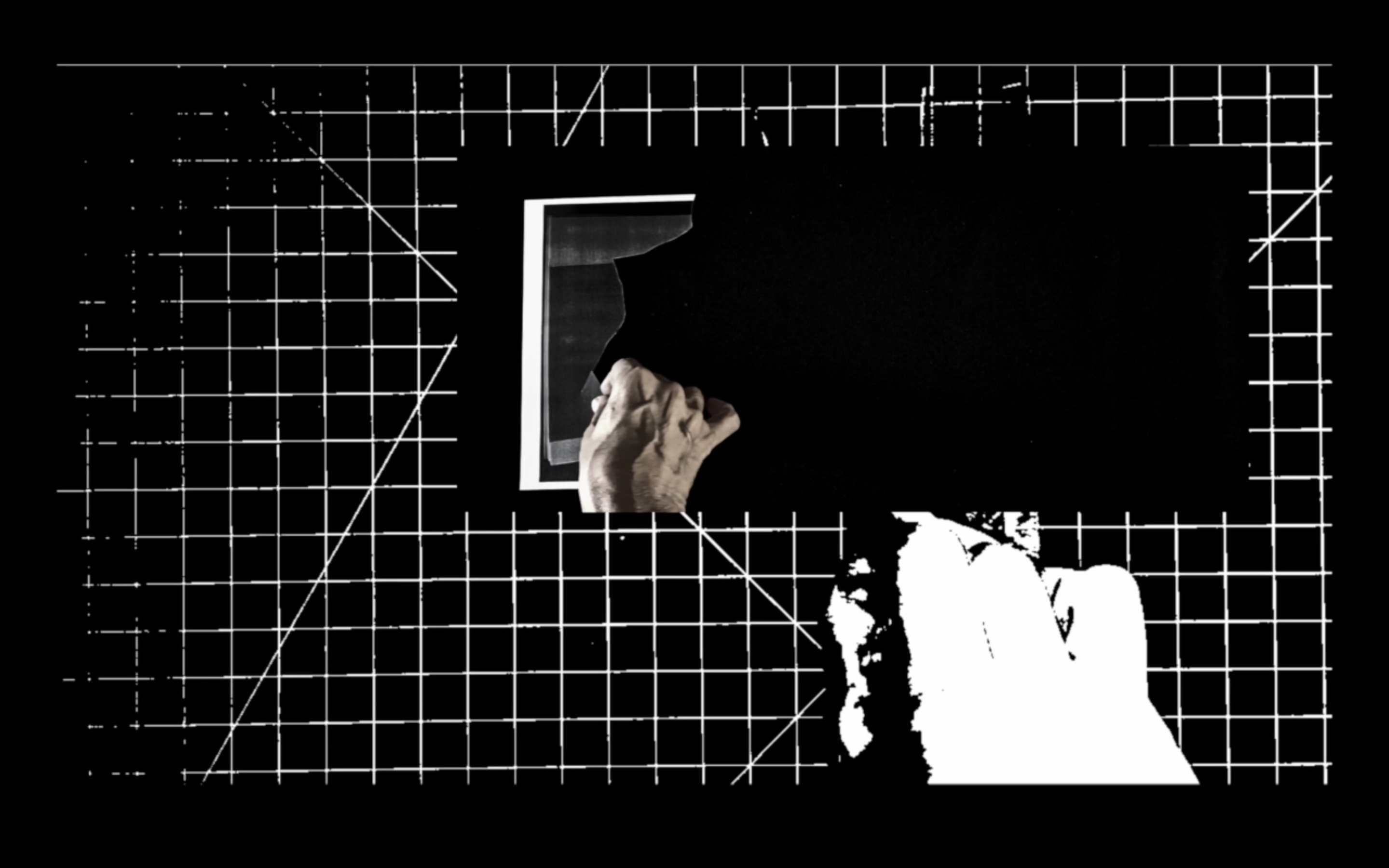

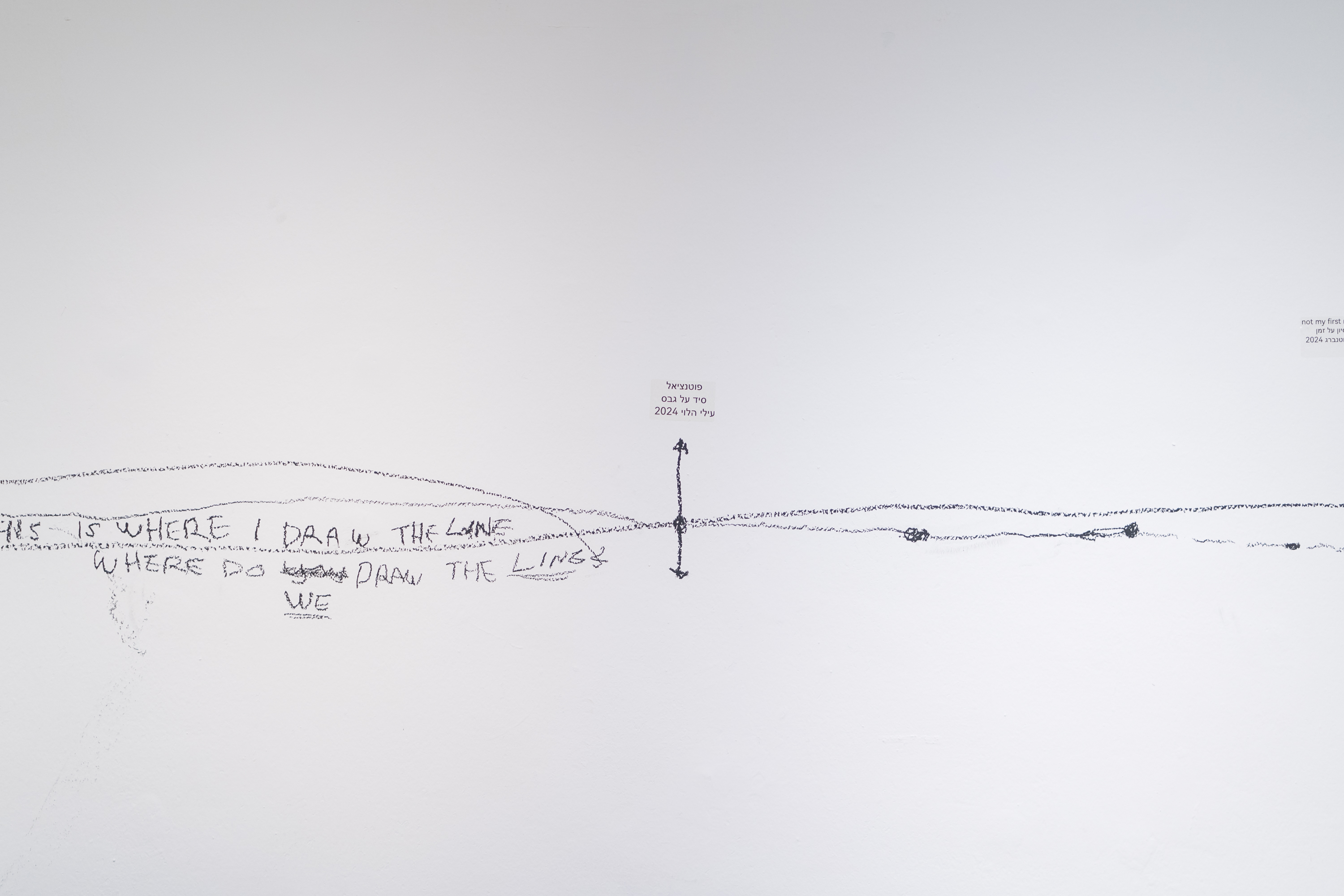

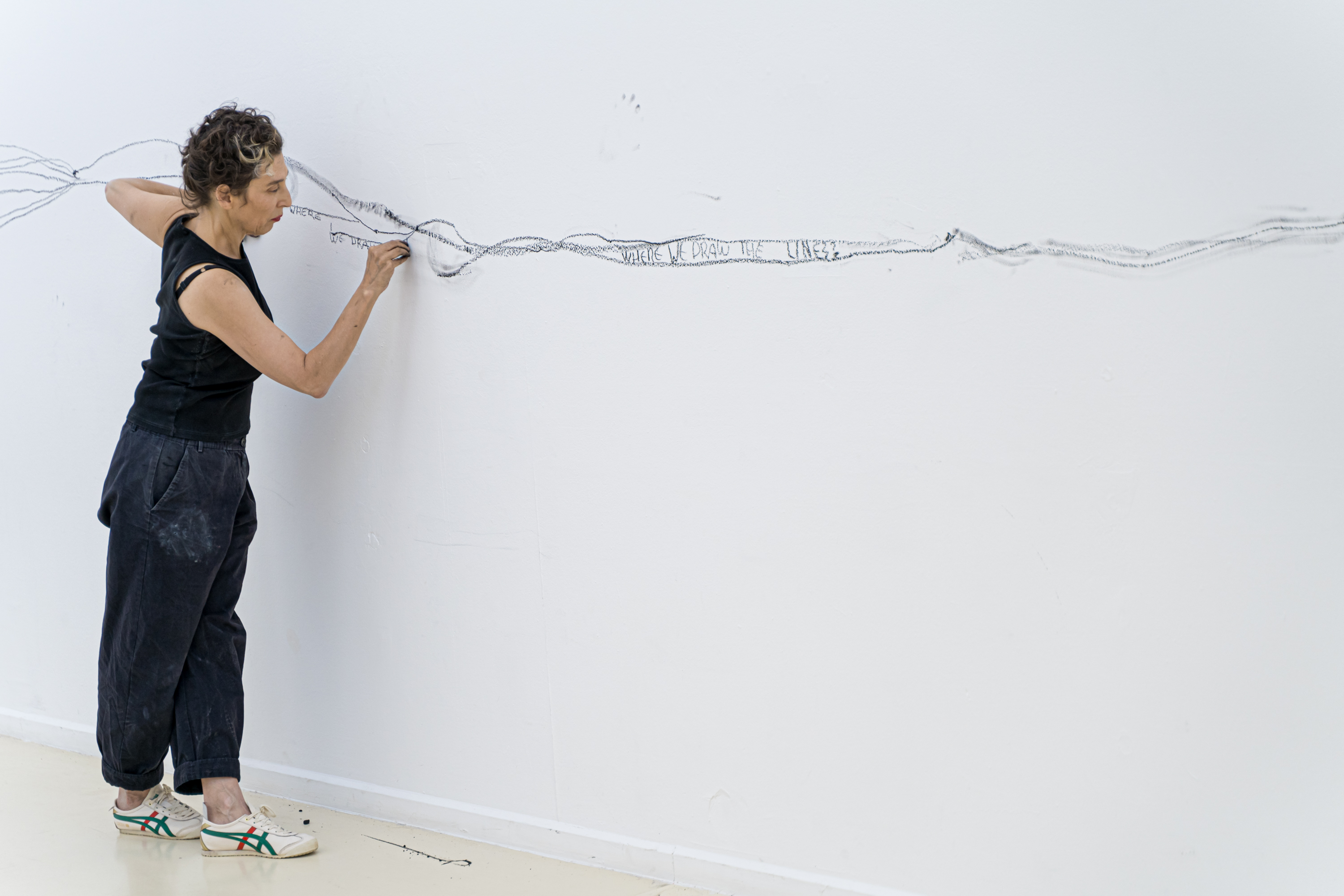

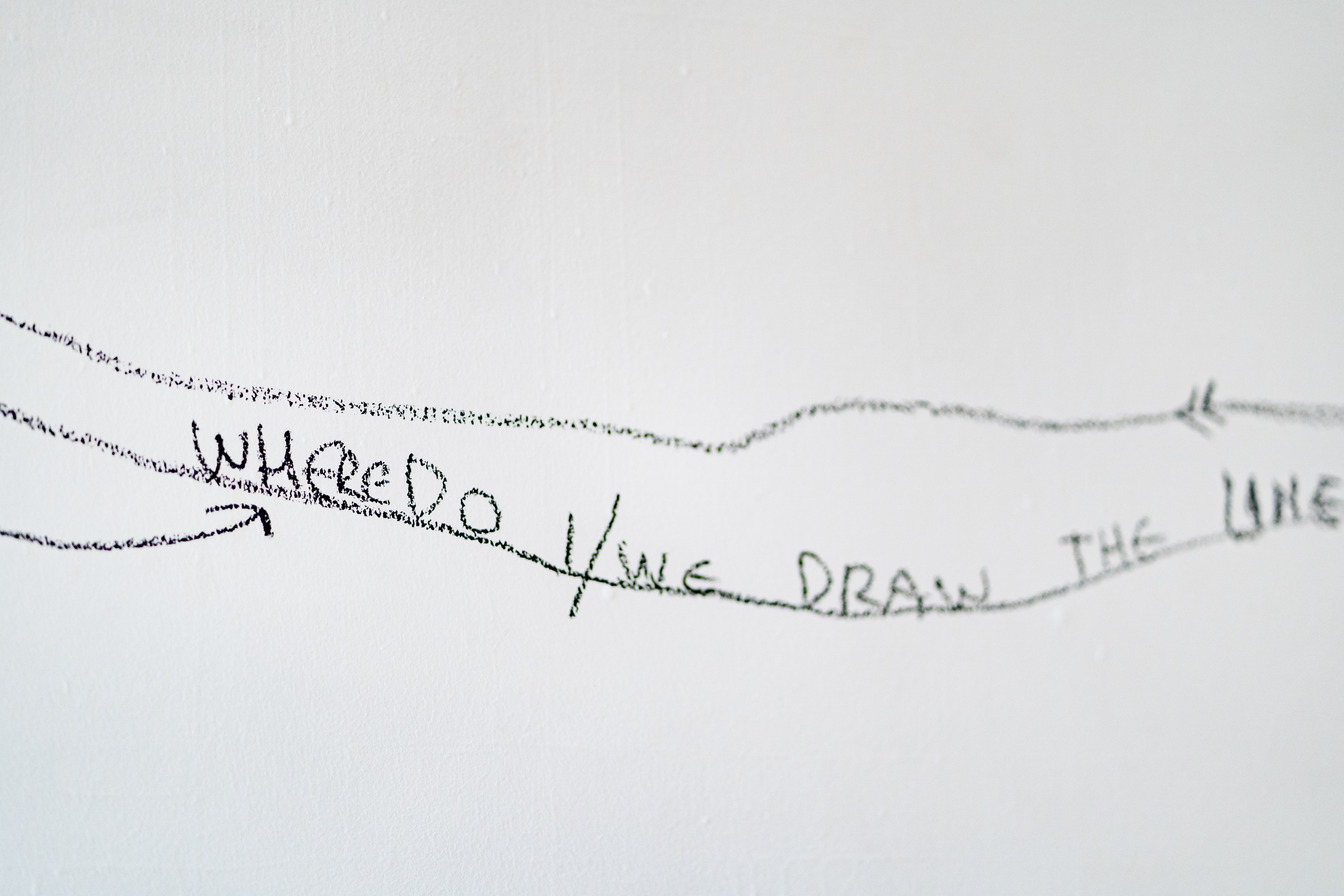

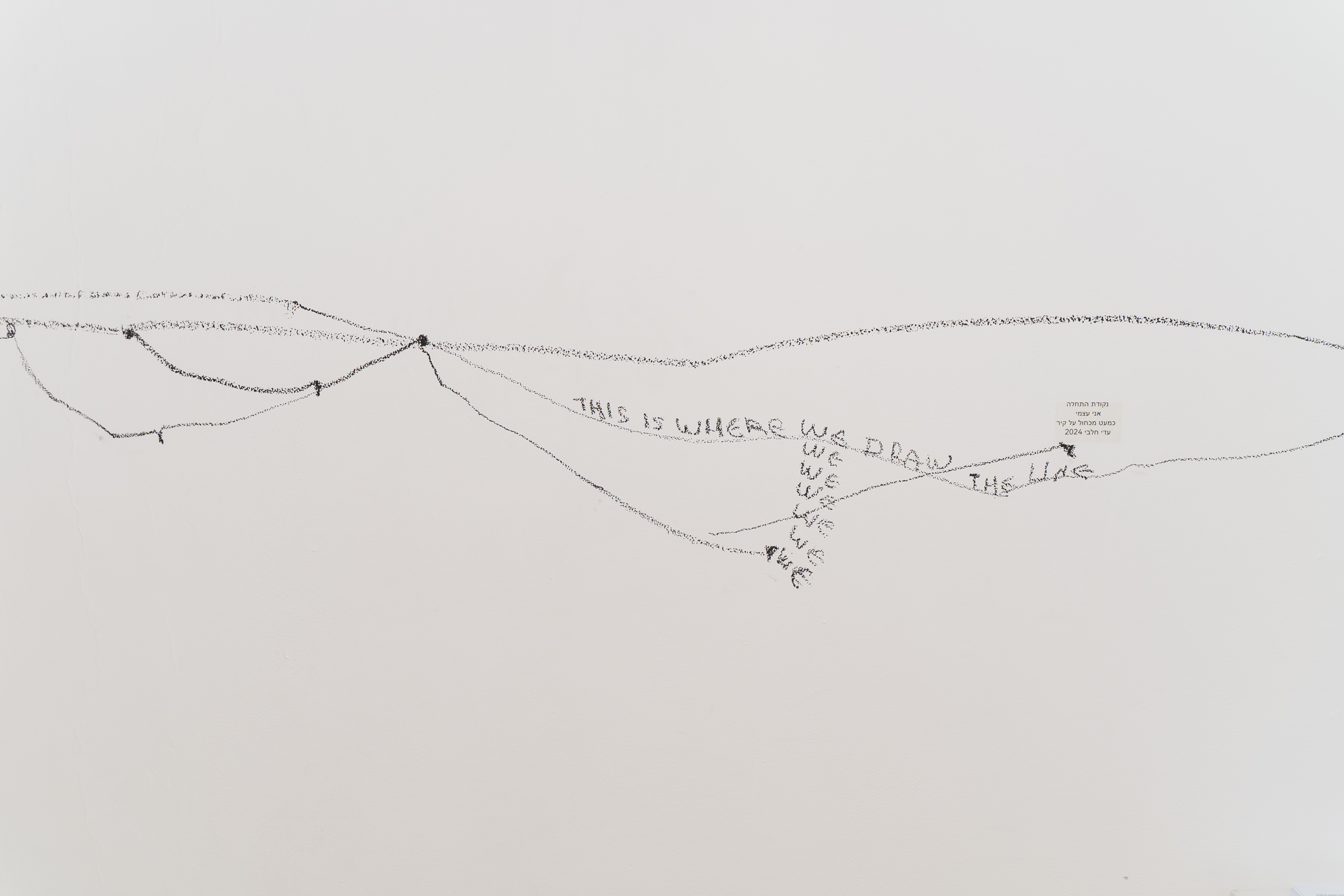

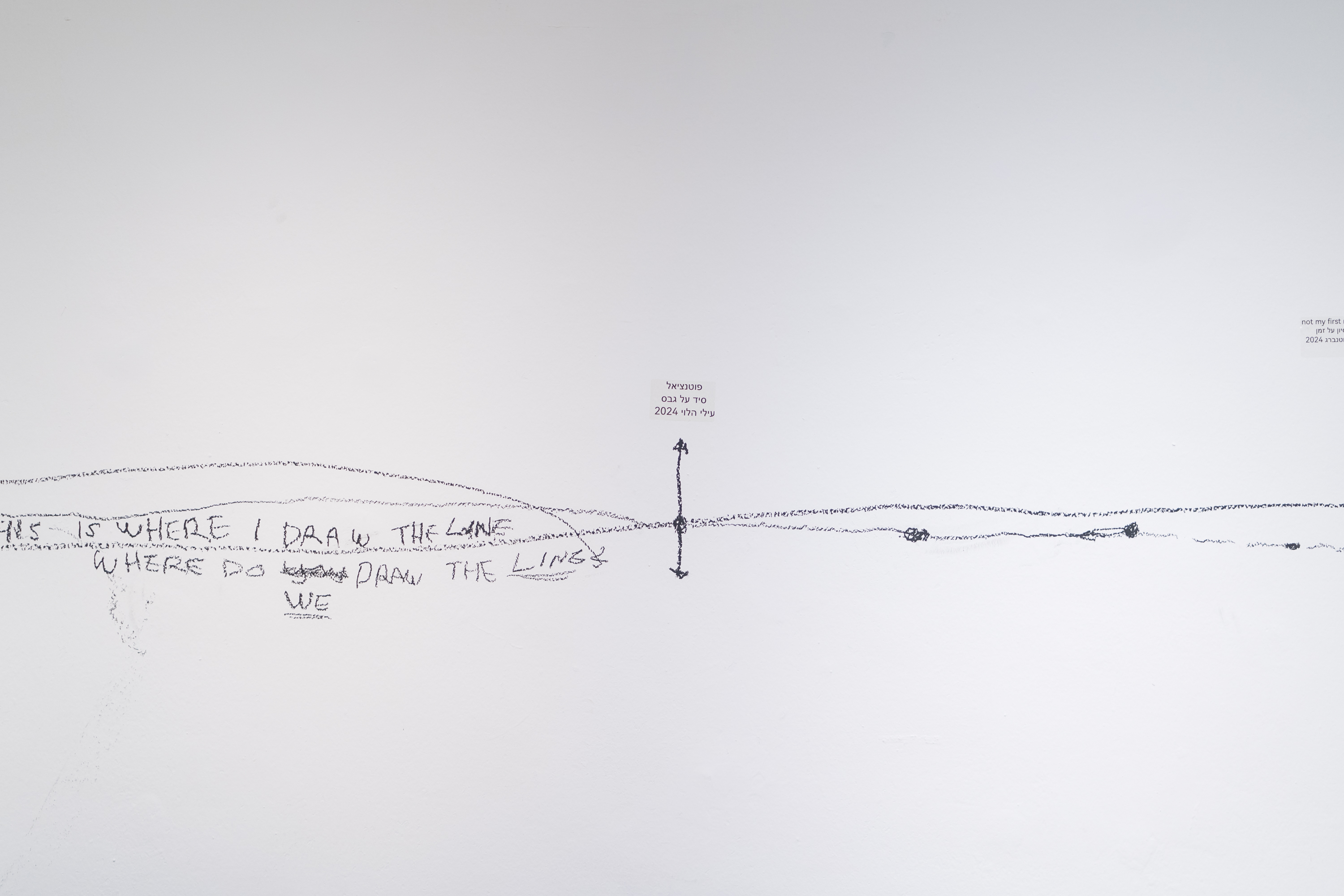

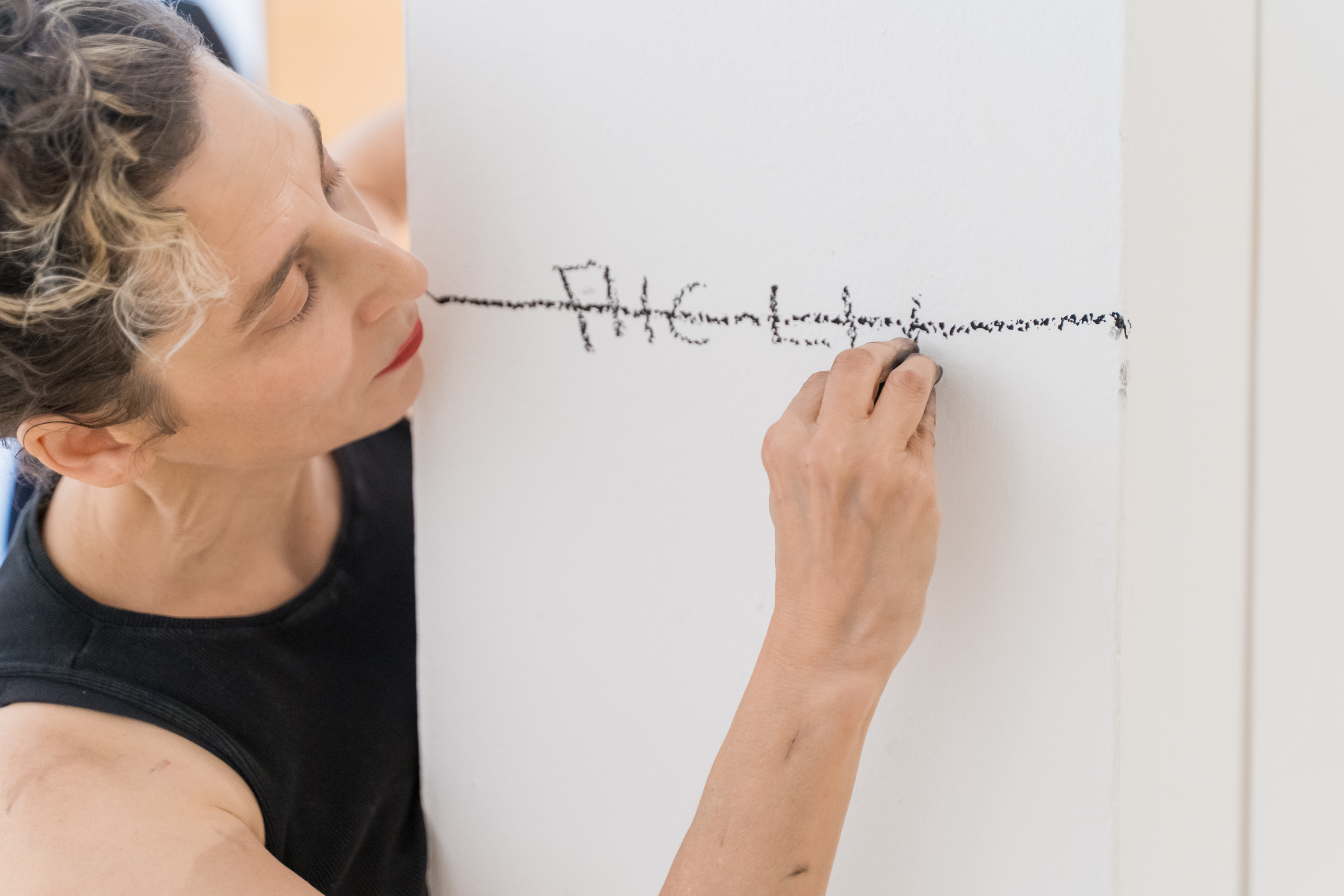

Live-Line, 2024

A four hours perfromance at the empty Herzlyia Museum of Art

How do we keep a line of thought or the horizon line in these very dark days?

a four-hours perfromance where I tried to maintain a line and thinking through the very basic yet highly political question of the moment: Where do we draw the line?

Ground Control: When The Horizon Becomes A Frontier

A single channel video, 16:36 m, 2023.

A single channel video, 16:36 m, 2023.

"A man goes to space. What sort of mathematical models, data protocols, physical training, herbs and pills, funding arrangements, anti-pressure medication, anti-depression medication, political infrastructures, financial abilities, personal objects and souvenirs, legal status, playlists and mix tapes, imperial desires, industry trades, and policy agreements move with him across the horizon line?"

InApril 2022, astronaut Eytan Stibbe spent eight days at the International SpaceStation. During this time, we corresponded daily and attempted to create avirtual tour of a place most people will not visit: space. If space used to be the horizon,it is currently becoming a new technological and economic frontier. The project responds to the politics of the new colonialtechnologies of reach—the “new space,” a rapidly developing techno-politicalarena that is undergoing an accelerated process of privatization.

Every morning, I sent the astronaut three sentences tospace. For each sentence, he replied with the photo. The images sent from spacebecame a starting a project that wondered, can we tour a placethat we will never visit? The project uses fictioning as a method to explore the co-presence of many different pasts and futures within a given landscape.

(00:26) from the movie “ground control”

(00:26) from the movie “ground control”

(01:36) from the movie “ground control”

(00:46) from the movie “ground control”

Testimonies of Things

Testimonies of Things is a series of experimental writing and photographic works motivated by the notion of non-human testimonies about the museum fire. The speculative series aims to splice scientific and poetic knowledges of in order to capture the transition from matter or bio form to the digital realm through the perspective of six entities.

1. Meteorite

Pedra do Bendegó travelled from space to the Brazilian region of Bahia, where it rested still on the ground for several thousand years. An irregular mass, 5,360 kilograms of iron covered by a ten-centimeter layer of oxidation, it has numerous depressions on its surface and cy- lindrical holes parallel to its greater length. Part of its lower portion was lost during landing and left a smooth surface on one face. Besides iron, the meteorite also consists nickel, cobalt, phosphorus, and traces of sulfur and carbon in much smaller quantities.

Ever since it first came into contact with human eyes, the iron has been on the move again. A boy called Domingos da Motta Botelho was grazing cattle on a farm near what is now the town of Monte Santo when he first spotted the meteorite in 1784. Even considering the slow local movement of people and commerce, the news of the finding spread quickly. In 1785, the region’s governor, D. Rodrigues Menezes, arranged for the meteorite to be transported to the city of Salva- dor, however, its weight made transportation difficult. The cart it was placed on lost control and the meteorite fell into a dry stream bed, 180 meters away from the spot where it was initially found. The meteorite didn’t travel with the people, but the people started to visit Bendegó. The London scien- tific academy the Royal Society published A. F. Mornay’s drawings of the meteorite in its periodical, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, and the first reproduction of the metal rock started to orbit the visual sphere. Seventy years later, the meteorite was lifted and rolled to the National Mu- seum of Brazil and stopped right by the door.

In the first room of the museum, past the armed personnel and the metal turnstiles, it rested on a pedestal for 130 years. Always the first thing in sight, the first image taken. Then the fire happened. No major damage. Standing still. Long lasting after the museum. The first room, behind the metal turnstiles, all covered with ashes from burnt neighboring objects. Images were uploaded and downloaded, links were shared, posts were posted. Pictures transmitted up toward space and back down to the Brazilian earth. What are the means with which the earth sees? After the ashes and images rested, I clicked on the link and entered the museum again. I passed the two blurry-faced armed personnel and glided through the metal turnstiles. On my way to the staircase, I dragged my cursor around and above Bendengó, smearing glitches with depressions and cylinder-shaped holes, forming a geo-digital irregular mass of image-matter.

2. Water

The line for the paddleboats was long. There were birthday tables decorated in matching colors and helium balloons. Young girls were posing in front of their cameras and tagging the Quinta. It was September, and spring was finally here. Quinta da Boa Vista was a farm surround- ed by mangroves and swamps, but Elias António Lopes, who built a manor house on top of its hill, had to donate it to the Portuguese Prince. The gift was much appreciated. Up the hill, the manor became a palace, that then turned into a museum of mankind. Down the hill, swamps turned into roads, and lands were curved into lakes to decorate the view from the palace. Animals were brought in from many parts of the world to roam around it. Peacocks, toucans, and swans. Two man-made containers of wonders and pleasures, open to some bodies. Then the fire happened. Uphill, worlds were burning fast, wing by wing. The first responders fighting the fire were hindered by insufficient water. The two fire hydrants next to the museum had no supply. An error. Everything slowed down. Never-ending minutes in the head of Colonel Roberto Robaday, who had to act fast. How do you extinguish a fire without water? It took two more hours until the firefighters started to pump water from the swamp. The Pedalinhos lake, where peacocks were piercing, and toucans were singing, and the swan-shaped paddleboats were always waiting. Facts and fables were rigged. Hoses and gate valves rolled and clicked, stretching the water between two containers of wonders.

For some time, the pressure in the fire hydrant was low, but the high pressure of real estate and industry developers didn’t stop pumping, bringing the system to the brink of collapse. This is a dry season for fire hydrants, and water pumps, and local reservoirs, and natural watersheds. For some time now, bodies of water have slowly been dehydrating under official priorities. For modern water, dry became a condition. The museum was an old building. An old building with all sorts of old lives, old debts, and no liquid assets. The government support dried out long ago. The city was busy building a brand new “museum of tomorrow.” It was a question of liquidity. Fire was the method.

3. Ashes

Through Rio de Janeiro’s night sky, ashes flew up to the air and fell on the ground. Burnt anthropoids and ancient cockroaches dropped in backyards. Employee surveys and rejected paperwork fell quietly on stoops and balconies, like foliage. Index cards landed on the neighbor’s front porch. Burnt particles from other lives took local flights, and touched down much closer to home. Ashes scattered and spread out the word, like silent witnesses carried by the whispering wind.

Pedro Luiz loves ashes and sarcophagi. Ashes are the best storytellers and sarcoph- agi are the best mystery. An expert on Egyptian monuments, he was brushing dust for a living. If you can call it a living. His work at the National Museum was like living in a giant, Russian doll–shaped sarcophagus. A memory chamber of all sorts of things that were once alive and are now kept in jars and glass cases, registrar forms and long lists, catalogues and exhibition shots, and photocopies. Many photocopies. Also, slides and films, tapes and floppy disks, and CD-ROMs and memory sticks that sometimes reminded him of specters. Moving between rooms and boxes, he imagined his work- place is a giant beast fed with dead life-forms and memory forms, each has a copy. But for Pedro, death is where life is, so life was good.

For a while now, Pedro has been using his tools to excavate his own workplace. Cof- fins and amulets, staples and line levels, and spectral memory sticks. New ashes consumed old ash- es, new death consumed old death. The matter that recorded the evidence of violence is devoured by its own materiality. Necro-metabolism. Pedro brushes, measures, and puts things in boxes. He thinks of the Sanöma people, who live in the Yanomami land, who destroy the marks of the dead by consuming their corporality. The meticulous practice of remembering in order to forget include drinking the liquids that came out of the deceased, pulverizing their bones, consuming the ashes, and eating the rest, mixed with banana porridge. The dead have a right to be forgotten. Their own deeds—forget them; their own lives—erase them; their belongings must be burned. The metabolic system is a hell of a mnemonic device. Pedro sticks boxes in rooms. A colleague tells him, “The origi- nal pieces that were there are part of our conquest through the struggles of our loved ones who are not here. Now we have memories, more than we live because they are live for us.” And Pedro thinks of living with them, with us, dead or alive. Ashes, ashes, we all fall down.

4. Skins

Tropical climate is good for composting, not so much for mummies. But for 600 years a twenty-five-year-old woman was buried in a cave in Minas Gerais until Maria José de Santana, the owner of a coffee farm, discovered her in perfect condition. Her skin still stretched like a gift wrap over her body. It was the nineteenth century, so Maria gave her ancient young sister to Dom Pedro II, who added the gift to his collection. It wouldn’t be the first skin that was given to Dom Pedro. Nor the first body. A Chilean man, who was buried seated was still sitting in a glass box. His knees are drawn under his chin, like a shy boy. His skin covers his body like a dry container.

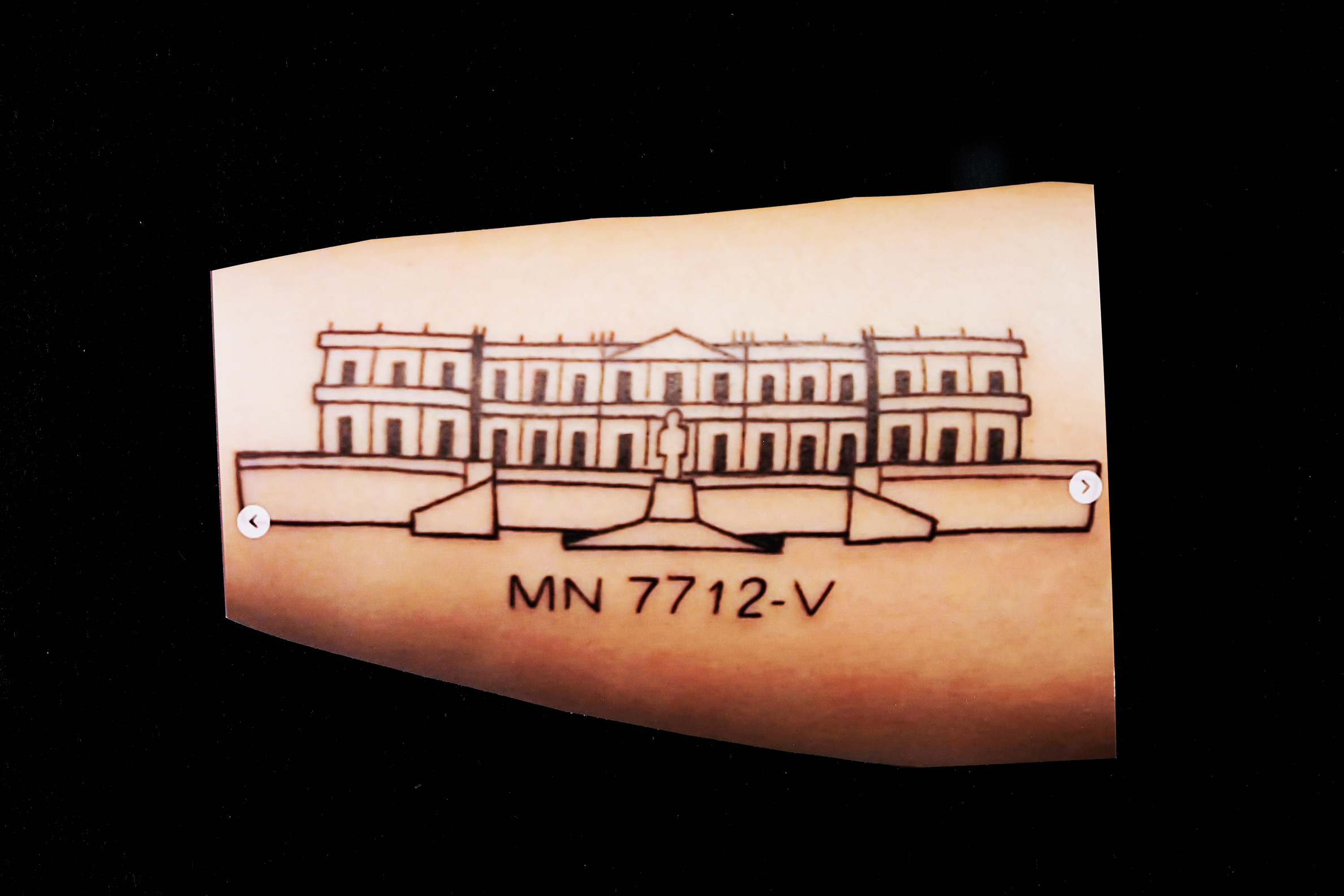

Then the fire happened, leaving scars all over. Inside the hazy galleries, a new skin starts growing. Skins were leaving their toxic bodies, growing like a free creature inside the great halls, smells of killing. The skin of the young woman from Minas Gerais comes off her bones; the Chilean mummy peels a layer from its folded cover; the mummified cat sticks to the snakeskin; burnt skins grow their own living mesh; and people started to ink the museum on their own skins. MN 7712-V. New black ink on the arm of paleontologist Beatriz Hörmanseder marked the serial number of a crocodile fossil they were studying. 06-06. A Quaternary Geographer, Suzanna Matos shared her birthday with the museum. The ritual of marking started small and grew via the social epidermis into a small movement, #museunapele. Entomologist Ivyn Sousa tattooed her lab’s win- dow bars, where toucans regularly landed. Architect Marco Hermann who planned the roof ren- ovation traced the blueprint of the museum façade. He kissed the ink before it dried. Their skins were faster than their words. A social skin was coming together, wearing the museum of mankind. The skin is witnessing. The rage is inked deep.

5. JPEG

A fragmented and eclectic digital collection survived from the ruins. The images, all taken by small interest groups and visitors, are now stored on their personal devices or on cloud services and are shared via social media. The photos became a portal to the very different data they were slowly aggregating: other images they saw, locations they checked in at, a personal library or- ganized by geolocation or facial recognition software, social networks, and other data points. Each file is named by its contributor. One is named «mollusks shells.jpg,» the other «Sofia and Dino11. jpg.» A new princess in what once was a palace, then a museum, and now a library of lossy-compres- sioned digital images. Copies in motion, squeezed into a 1:10 ratio. Ripped many times over. Does a JPEG has a memory? There is also a virtual tour, a product of Google Arts & Culture, where one can visit the no-longer-existing museum. No more boxes and cabinets, the objects are now robbed of the capacity to be present. They are stored through the same interface as your street.

6. Cursor

Screens remained on all night, measuring in real time the ever-growing black cloud above the palace. Talking heads were stuttering broken sentences that were not translated. Cur- sors moved forward and backward, typing words with such lightness, as if writing and deleting were equally painful. Sometimes, all one can do is watch the fire. The internet seemed to be working. DrawIn, the user who just created a Wikipedia page dedicated to the fire, got to the museum before the firemen. With others, he started copying the database, folder by folder, collecting the data from the ruins. By midday the database was suddenly gone. Things that are gone have less of a chance to ruin elections and the elections were only a month away.

In one room, Sala Kumbukumbu, dedicated to Afro-Brazilian cultures, they collected 1000 individual records. Kumbukumbu, a word that means “objects, people, or events that make us think about the past.” My cursor is scrolling down the database, then dragging me around the room. My cursor is a runner, a moving body without flesh, motivated by language. It stops at the room where the people are gone, and the objects are robbed, and the language is broken: Ob jjject spe pleore v entst-hatma ke u ssssth ink aboutttt thepassssst. My cursor is holding things together by keeping my words apart. My cursor interrupts. It tells me when action is needed. A tilted arrow, with an extra pixel on top, pointing toward the things that make us think about the past.